Two days. That’s how long it took to build a scoring engine that does 165 million lookups per second. I’m still not entirely sure whether I built it or merely uncovered it, like a trapdoor in my own floorboards.

And yes, the name matters. This thing is an all seeing eye.

This was not intended to be a series of blogs, but now that it has become one, here is some context (just in case you want the back story) . . .

Part One: https://iamnor.com/2025/08/07/claude-c-and-carnage-building-log-carver-at-the-edge-of-performance/

Part Two: https://iamnor.com/2025/08/24/claude-c-and-carnage-part-ii/

Not the melodramatic kind. The practical kind. The kind that can glance at every IP at wire speed and decide whether the packet deserves scrutiny, or just deserves to get out of the way. Most of the internet is boring. Most of your traffic is boring. Most addresses are unscored darkness. The trick is learning how to not touch anything for those cases.

I’ve been building scoring engines for years. The pattern is always the same: you need to track risk scores for IP addresses, you reach for a db or Redis, you build some wrapper code, you tune the connection pool, you benchmark, you optimize, you accept that network latency is the cost of doing business. I’ve done this dance enough times that I could do it in my sleep. Redis works. It’s battle-tested. It’s what serious people use.

But I’ve been building Specter_AI, and Specter_AI has a problem. It can process somewhere between 50 and 120 million network events per minute, depending on what’s happening in the environment. Each event usually contains multiple IP addresses. Each of those IPs needs context: is this address a known threat? Has it been behaving suspiciously? Is it part of infrastructure we trust? The downstream analysis pipelines are expensive. Machine learning models, behavioral analysis, correlation engines, none of that is cheap, and throwing all of it at every single event is wasteful when most events are just normal traffic doing normal things.

The hypothesis I’ve been chasing is simple: what if we could pre-filter? What if, before an event enters the expensive analysis pipelines, we could ask a single question: what do we know about these IP addresses right now? Then use that answer to route events appropriately. Suspicious source IP? Full analysis. Known-good infrastructure? Fast path. Novel address with no history? Maybe somewhere in between.

This is the kind of situational awareness every good analyst carries around in their head. The difference is I needed it at machine speed, millions of times per second, without turning the “pre-filter” into the new bottleneck.

Redis gives you answers in microseconds. That sounds fast until you do the math. At 2 million events per second, even a 100-microsecond lookup means you’re spending 200 seconds of CPU time per second just on score lookups. Even spread across cores, you’re still buying a CPU farm just to ask a key-value store a question. That’s not a bottleneck. That’s a wall.

I needed nanoseconds. Not microseconds. Three orders of magnitude faster.

I didn’t expect this to work

I’ve written about vibe coding before, this process of collaborating with Claude to build systems faster than I could alone. The honest assessment from those experiences: it’s a productivity multiplier, but it’s not magic. Claude generates plausible code quickly. Claude also hallucinates, deletes important things while “simplifying,” and suggests the same broken patterns session after session because it has no memory of what failed yesterday. The expert human stays in the loop or the code turns to slop.

So when I sat down to build a custom scoring engine in C, not a wrapper around something else, but the actual data structures and hot paths, I expected the usual grind. A few days of productive collaboration punctuated by hours of debugging Claude’s mistakes. A week to get something working. Another week to make it fast.

Instead, I got something that compiled, passed tests, and benchmarked into “this can’t be real” territory fast enough that my first reaction was suspicion.

The architecture: don’t touch memory you don’t need

The first day was architecture. I’ve tried enough approaches over the years to know what doesn’t work. A flat array covering all of IPv4 would consume gigabytes of RAM. A hash table adds overhead and cache misses. A trie means pointer chasing, and pointer chasing means latency.

The insight came from thinking about what I was actually trying to do. In production, the vast majority of IP addresses have no score. They’re just traffic. Clean, boring, unremarkable. If 80 or 90 percent of lookups return zero, why am I touching score data at all for those cases?

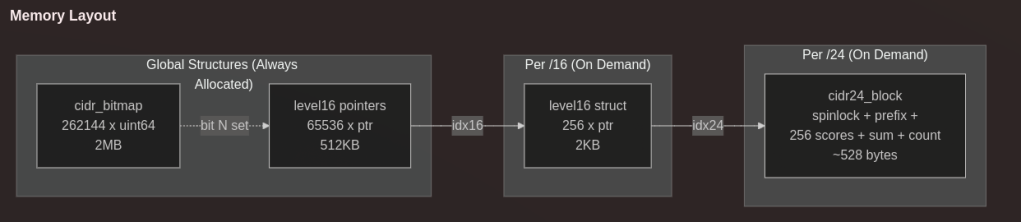

A bitmap. 2 megabytes. One bit per /24 network. Before looking up any score, test a single bit. If it’s zero, return immediately. No pointer chasing. No cache misses. Just a bit test that fits in L3 cache and completes in a handful of cycles.

For the remaining 10 or 20 percent, the addresses that actually have scores: a two-level structure. /16 arrays point to /24 blocks, each containing 256 scores. The hot paths stay cached. The cold paths hit memory, but they’re rare enough that it doesn’t matter.

Here’s the whole shape in one glance:

I explained the design to Claude. Claude wrote the code. I reviewed it, found the usual issues (missing error checks, overly clever abstractions that would hurt performance), and we iterated. By the end of day one, I had something that compiled and passed basic tests.

I didn’t run benchmarks yet. I was afraid to.

Benchmarks, and the part where the universe acts suspiciously

Day two started with benchmarks, and this is where the story stops making sense.

The target was 2 million operations per second. That’s what I needed. That’s what I would have been happy with. Two million ops/sec would mean score lookups were negligible overhead compared to everything else Specter_AI does.

The first benchmark came back at 39 million ops/sec for writes. I assumed I’d made a measurement error. I ran it again. Same number.

Reads, the lock-free path through the bitmap, came back at 165 million ops/sec.

I stared at the numbers for a while. Then I ran the benchmarks again. Then I added more tests to make sure I wasn’t somehow fooling myself. The numbers held.

Multi-threaded benchmarks pushed reads to 687 million ops/sec across 8 cores. Decay operations, walking through every score and applying a multiplicative factor, processed 738 million scores per second.

I’ve been building performance-sensitive systems for a while. I’ve never accidentally built something dramatically faster than I needed. You fight for 10 percent improvements. You celebrate 2x speedups. You don’t usually wake up to two orders of magnitude of headroom.

But here’s the thing: there’s no sorcery here. The bitmap filter is a known trick. Lock-free reads with atomic loads are the boring, reliable kind of fast. Per-block spinlocks for writes are standard practice. None of this is new. The difference is I finally arranged it like I meant it.

Maybe the real question isn’t how I built something this fast. Maybe the question is why I spent years paying the “microseconds are fine” tax when I didn’t have to.

The rest of the day was trying to break it

Once the benchmarks looked real, the job changed. Now it was a demolition exercise.

I added features: bulk loading from CSV files, batch increment operations, iteration over all scored IPs. Each feature was a chance to introduce overhead, and I watched the benchmarks like a hawk.

Some things worked fine. Some things didn’t.

I got excited about SIMD optimization for the decay loop. 256 consecutive int16 values, all getting multiplied by the same factor. I implemented it with AVX2 intrinsics, Claude helping with the arcane syntax. It worked, mostly. But edge cases around floating-point precision caused off-by-one errors, and off-by-one errors in scores mean incorrect blocking decisions. I spent hours trying to fix it with fixed-point arithmetic. The bugs just moved around. Eventually I deleted the whole thing. The compiler was already auto-vectorizing the scalar loop reasonably well. Premature optimization of the optimization is still premature optimization.

I added configurable IP filtering: bogon ranges, RFC1918, custom ignore lists. Elegant, sensible, completely reasonable. It murdered write performance by 39 percent. The check ran on every single write, and the overhead of the function call, the loop over the ignore list, the conditional branches… death by a thousand cycles. I ripped it out. Filtering is the caller’s responsibility. The scoring engine scores IPs. That’s it. Do one thing well.

I asked Gemini to review the architecture. The report was thorough and professional and confidently warned about a race condition in my memory management, readers accessing freed blocks during decay. I spent time preparing to implement hazard pointers before I actually traced the code and realized the race condition was impossible. Blocks are never freed during decay. They’re zeroed, but the memory stays allocated until context destruction. The review was wrong about the most critical part of the system. External reviews are valuable, but verification beats trust.

So why doesn’t every system have this?

Here’s what I keep coming back to: why doesn’t every system have this?

Situational awareness of the threat landscape, real-time understanding of which IPs are suspicious, which are trusted, which are novel, is foundational to security operations. Every SOC analyst builds this mental model intuitively. Every threat intel platform tries to capture it. Every SIEM correlates against it.

But the actual mechanism for querying this knowledge at machine speed, millions of times per second, integrated directly into event processing pipelines? That’s rare. People reach for Redis, or Elasticsearch, or some other external service, and they accept the latency because that’s what you do.

I accepted that latency for years. Now I have a library that answers the question in nanoseconds, and I’m wondering what else I’ve been leaving on the table.

The immediate application is Specter_AI: pre-filter events based on IP reputation, route suspicious traffic to expensive analysis, fast-path the boring stuff. But the principle generalizes. Any system processing network events at scale could use this, anywhere you’re making per-packet or per-flow decisions and you have context about addresses that should inform those decisions.

165 million lookups per second. 540 bytes per active /24 network. Lock-free reads. The whole thing fits in a shared library smaller than most profile pictures.

And yes, I still built it in two days, collaborating with an AI that doesn’t remember what we did yesterday and occasionally tries to delete my optimizations. The multiplier was real. But the architectural decisions, the performance intuition, the constant benchmarking and verification, that was human judgment applied to machine-generated code.

The code is open source. GPLv3. 135 tests. If you’re processing events at scale and need fast answers about IP reputation, maybe it helps. If you find bugs, tell me. If you think the approach is fundamentally wrong, I’ve been called worse things.

And before someone asks: what about IPv6?

IPv6 is the elephant in the room. The bitmap trick works because IPv4 has boundaries you can treat like a map. IPv6 is a universe of sparse, shifting constellations. You can still score prefixes, you can still build sparse structures, you can still do “fast no” gating, but you don’t get the same clean “one bit per /24” cheat code. That’s a different engine, and it deserves its own fight.

The scores still get looked up in nanoseconds. For a project that started as “let’s pre-filter some events so my expensive pipelines stop eating themselves,” I’ll take it.

If you’re still paying a microsecond tax on the hot path because “that’s what everyone does,” consider this your invitation to stop.

Leave a comment