It started in a car.

Somewhere on a highway en route to a vendor meeting, packed in with a few other security professionals; Marcus Ranum, Tom Liston, and a couple of us who probably should’ve been paying more attention to the GPS, we got into a heated, hilarious, and somewhat sincere debate:

“How far will we go to isolate bad code and programmers?”

We laughed but mostly ranted. We all had scars; stories of kernel panics caused by a single misplaced pointer, firewall rules written by the optimistic, and enterprise applications that assumed root was just the default. By the time we pulled into the parking lot, we had mapped out what could only be described as a defensive arms race against bad programming, an architectural response to human fallibility.

That conversation never really ended. It’s come up over beers at conferences, inside threat modeling sessions, and in the code review comments no one wants to admit are real. And it turns out, the history of computing itself is, in large part, the story of protecting systems from ourselves.

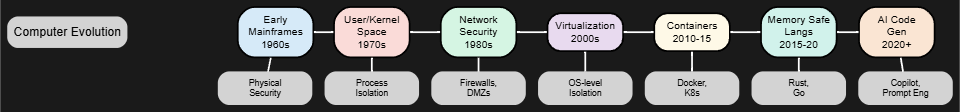

What follows is a technical and mildly exasperated tour through the milestones of computing—all viewed through the lens of architectural and systemic efforts to contain, isolate, and survive poor code.

In the Beginning:

There was trust. Blind, dangerous trust. The earliest mainframe computing systems, massive iron giants housed in pristine, chilled rooms, executed every instruction in the same privileged memory space: the kernel. These were systems like the IBM System/360 (introduced in 1964) where all code was effectively root code. There were no guardrails between programmer intent and system integrity. If a COBOL or Fortran subroutine dereferenced the wrong pointer or corrupted memory, it wasn’t just the application that failed; it was the entire machine.

Security, in that era, was physical. Protect the room, protect the machine, and implicitly, you’ve protected the computation. But as systems became more complex, this naïve model collapsed under its own weight.

User Space: The Birth of Containment (1970s)

To mitigate the systemic risk of errant or malicious code, the concept of user and kernel mode emerged in academic and commercial systems. The Multics operating system (developed in the mid-1960s, deployed broadly by the 1970s) introduced the idea of ring-based privilege separation (Saltzer & Schroeder, 1975).

UNIX, released in 1971, implemented a simpler but effective two-mode architecture: kernel mode and user mode. This architectural shift formed the basis of modern process isolation.

Now, a bad pointer in a user program could crash a process, but it wouldn’t crash the machine. This was the first real defense against poor programming—not through better code, but through better execution context.

Networked Computing: Trust, But Don’t Share (1980s–1990s)

By the 1980s, with the rise of ARPANET and eventually TCP/IP–based networking (standardized in 1983), computing systems became interconnected. Suddenly, your code wasn’t the only code running on your system—remote input became a real threat vector.

This shift led to the birth of network segmentation, perimeter firewalls (first commercial firewall: DEC SEAL in 1992) (Cheswick et al., 2003), and concepts like DMZs and bastion hosts. Operating systems introduced user-level permissions, discretionary access controls, and eventually mandatory access control frameworks like SELinux (released in 2000 by the NSA).

The key takeaway: isolate what doesn’t need to touch each other, not just logically but network-wise. And never assume the code reaching your system was written by a friend.

Virtualization: The Hypervisor as Sentinel (2000s)

The early 2000s saw the rise of x86 virtualization as a security and scalability enabler. While virtualization traces back to IBM mainframes in the 1970s, it reached commodity infrastructure with VMware Workstation (1999) and VMware ESX Server (2001).

Hypervisors like Xen (released 2003) (Barham et al., 2003), KVM (2007), and Hyper-V (2008) allowed complete OS-level isolation on a single machine. Now, a rogue application couldn’t just take down a system; it couldn’t even escape the virtual machine it lived in.

Virtualization changed incident response too: snapshots, live migration, rollback, and clone testing became standard defenses. Virtualized micro-perimeters became possible.

Rant Intermission: The Abstraction Avalanche

Let’s take a breath as I don’t want this to come across as a Ranum rant (though I do really love to watch and read Marcus when he is fired up).

If you’ve made it this far, congratulations, you’ve survived a minefield of architectural fireworks: VMs, containers, namespaces, hypervisors, Kubernetes fleets, self-healing services, ephemeral compute nodes, and security policies defined in YAML so unreadable it should come with a health warning.

At this point, it’s worth zooming out and asking: where exactly is the system anymore?

There’s a famous line attributed to Rob Pike (or someone equally quotable in the pantheon of computing legends):

“Every problem in computer science can be solved by another layer of abstraction.”

“…Except, of course, for the problem of too many layers of abstraction.”

Each abstraction we’ve introduced was meant to simplify, to hide the messy, grotty internals and give developers a cleaner interface. But what we’ve really done is build towers of Babel. Every layer hides another set of assumptions. Every simplification conceals risk.

At one point, virtualization made system administrators feel redundant. Then containers made systems ephemeral. Then Kubernetes made deployments self-healing. But if everything is disposable, where does accountability live?

A close friend once sat on a Technical Advisory Board where a team was using Kubernetes as their security model. The idea was clever: “We can’t prevent all vulnerabilities, but we can patch at scale, instantly. Spin down, spin up, and keep moving.”

Cool idea. But then someone pointed out:

“Your actual problem isn’t fixing the vulnerabilities—it’s finding them.”

The conversation quickly devolved into an unspoken turf war between sysadmins, devs, and the DevOps unicorns expected to do both. He made the mistake of suggesting that maybe, just maybe, development and systems operations are different skill sets; and that giving devs root on everything might just give them one more thing to be bad at.

They canceled the advisory board after that.

And honestly? Who could blame them. Because the truth is: we’re just not very good at doing the things we do. Not reliably. Not consistently. Not at scale.

So, we keep abstracting. We keep building systems that assume we’ll fail and try to survive our failure. And every few years, we rename the problem, change the packaging, and pretend it’s a solution.

Okay. Deep breath. Intermission over.

Now back to the rant timeline.

Containers: Isolation Without the Baggage (2013–2015)

Then came containers: the diet version of virtualization. While virtualization offered OS-level isolation, containers offered process-level isolation in user space, using native Linux kernel primitives like cgroups and namespaces. The concept wasn’t new; chroot goes back to 1979, and Solaris Zones were doing something similar in the early 2000s, but the arrival of Docker in 2013 made containers portable, developer-friendly, and operationally efficient (Merkel, 2014).

Suddenly, you could isolate applications without booting full virtual machines. Containers spun up in milliseconds, consumed less memory, and became disposable by design. You could now deploy a misbehaving app, test it, observe it, and destroy it before it had a chance to do real damage.

And of course, we ran them on top of virtual machines, because we trusted containers to isolate apps, but not necessarily to isolate tenants or workloads at the infrastructure level. So, we stacked our abstractions like an insecure Jenga tower: containers inside VMs on top of hypervisors on top of bare metal. Because if one layer didn’t catch the mistake, surely five more would.

Kubernetes (released 2014) took this further (Hightower et al., 2017), turning collections of containers into orchestrated fleets, complete with declarative policies, sidecars, and automated recovery. That’s when we stopped just isolating apps; we started treating them like cattle, not pets. And yes, they still got compromised but now we could automatically kill and replace them, like some sort of self-healing swarm.

Memory-Safe Languages: Securing the Syntax Itself (2010s–Present)

Around 2015, the security community turned its attention to the root cause of most of the software vulnerability: unsafe memory handling in C and C++.

Google’s Project Zero and Microsoft’s Security Research Center began publishing consistent evidence that memory safety bugs (buffer overflows, use-after-free, etc.) accounted for over 70% of critical CVEs in their ecosystems (Microsoft, 2019).

Enter Rust, first released in 2010 and reached stable version 1.0 in 2015. With a strict ownership model, zero-cost abstractions, and no garbage collector, it promised C-like performance with far greater safety.

By 2022, both the NSA and CISA formally recommended shifting to memory-safe languages (NSA, 2022).

Other examples include:

- Go (released by Google in 2009), ideal for concurrent server-side logic

- Swift (Apple, 2014), replacing Objective-C in mobile environments

Critical infrastructure projects—like Amazon’s s2n TLS library and components of the Linux kernel—began to adopt Rust as a secure-by-design alternative (Anderson, 2022).

Microservices: Shrinking the Blast Radius (Mid-2010s)

Monoliths were too risky. A vulnerability in one module could compromise the entire application. Enter microservices, driven by container technologies like Docker (released in 2013) and orchestrated by Kubernetes (2014, donated to CNCF in 2015) (Fowler & Lewis, 2014).

Now, application components are isolated in lightweight containers, each running with just enough access and resources to do their job. Poor programming still existed—but it was caged.

Service meshes (e.g., Istio, Linkerd) brought observability, encryption, and policy enforcement between services. Identity-aware proxies and zero-trust principles turned every internal interaction into a potential security checkpoint.

Generative AI and Prompt Engineering: Vibe Check for Code (2022–Present)

In 2022, large language models like Codex (OpenAI, 2021) and AlphaCode (DeepMind, 2022) showed the ability to write complex software from natural language prompts. The age of prompt engineering began; not just code generation, but guided, contextual software composition.

In security terms, this is both promising and perilous. With tools like GitHub Copilot, developers can now generate code faster but also propagate flawed patterns just as quickly. The hope is that well-engineered prompts and integrated security tooling will eventually standardize best practices during code inception, not just code review.

Security-aware AI assistants now:

- Flag dangerous constructs in real-time

- Recommend secure APIs and libraries

- Integrate with SAST/DAST workflows

Still, prompt injection, AI hallucination, and supply chain poisoning of AI-generated code are active research threats (OWASP, 2023).

Conclusion

Throughout the history of computing, we’ve never truly solved the problem of poor programming. We’ve just contained it. Each evolutionary leap: kernel separation, process isolation, virtualization, memory-safe languages, microservices, and now generative AI, has been an attempt to minimize the blast radius of human error.

The future isn’t about trusting developers to write perfect code. It’s about continuing to build systems that assume they won’t; and making sure those systems fail safely when they inevitably don’t.

Of course, one might pause and wonder: could there have been a simpler, cheaper, and more elegant solution? What if (just hypothetically) we invested in highly skilled, deeply experienced software engineers? What if we compensated them well, gave them enough time to design thoughtfully, test rigorously, and write code with care? What if deadlines weren’t dictated by quarterly OKRs but by actual quality thresholds?

It’s a provocative idea. But then again, who has time for that when we can spin up ten thousand containers, deploy a mesh network, run static analysis in CI/CD, fuzz test the endpoint, isolate it in a VM, monitor it with AI, and still hope nobody notices the race condition in the logging function?

So, we build for failure, because betting against human error is historically a losing proposition.

— Ron Dilley

References

- Saltzer, J. H., & Schroeder, M. D. (1975). The Protection of Information in Computer Systems. Proceedings of the IEEE.

- Cheswick, B., Bellovin, S. M., & Rubin, A. D. (2003). Firewalls and Internet Security. Addison-Wesley.

- Barham, P., Dragovic, B., et al. (2003). Xen and the Art of Virtualization. SOSP ’03.

- Merkel, D. (2014). Docker: Lightweight Linux Containers for Consistent Development and Deployment.

- Hightower, K., Burns, B., & Beda, J. (2017). Kubernetes: Up & Running. O’Reilly Media.

- Microsoft. (2019). A proactive approach to more secure code.

- NSA. (2022). Software Memory Safety – Cybersecurity Information Sheet.

- Anderson, J. (2022). Rust in the Linux Kernel. LWN.net.

- Fowler, M., & Lewis, J. (2014). Microservices. martinfowler.com

- OpenAI. (2021). Codex Technical Report.

- DeepMind. (2022). Competitive Programming with AlphaCode.

- OWASP. (2023). Top 10 for LLM Applications.

Leave a comment