What is deception?

Our adversaries are in the business of lying, cheating, and stealing. Cyber deception is the creative and artistic application of misinformation, rule bending and deprivations to reduce risk. Success requires a holistic mindset intent on confusing, frustrating, and subverting those who wish to do harm.

Put yourself in the attacker’s shoes, gain understanding of what they intend to do and how they plan to do it. Implement both tactical and strategic deceptions to interfere with them while making it simple to detect.

| NOTE | de·cep·tion/dəˈsepSH(ə)n/noun the action of deceiving someone. “obtaining property by deception” a thing that deceives. “a range of elaborate deceptions” |

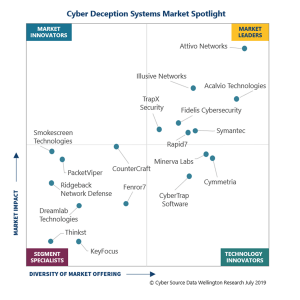

The deception market has taken off in recent years with a noteworthy number of vendors now offering capable and feature rich solutions.

Figure 1. 2019 Deception magic quadrant from Willington Research

The signal-to-noise ratio problem

Finding the bad people is hard because everyone is working and going about their daily lives across all the networks, systems, services, and applications at the same time as attacks are happening. Telling the two apart is very difficult.

Arguably, poor signal-to-noise ratios are the most significant problem that we face as cyber security practitioners. Companies spend a breathtaking amount of resources deploying and maintaining capabilities that provide poor signal-to-noise ratios and negatively impact the ratio overall by generating more anomaly and threat related events that after analysis, don’t represent signals. Fundamentally, only bad, or broken things interact with deception technologies. Because of that, the signal-to-noise ratio will always be high.

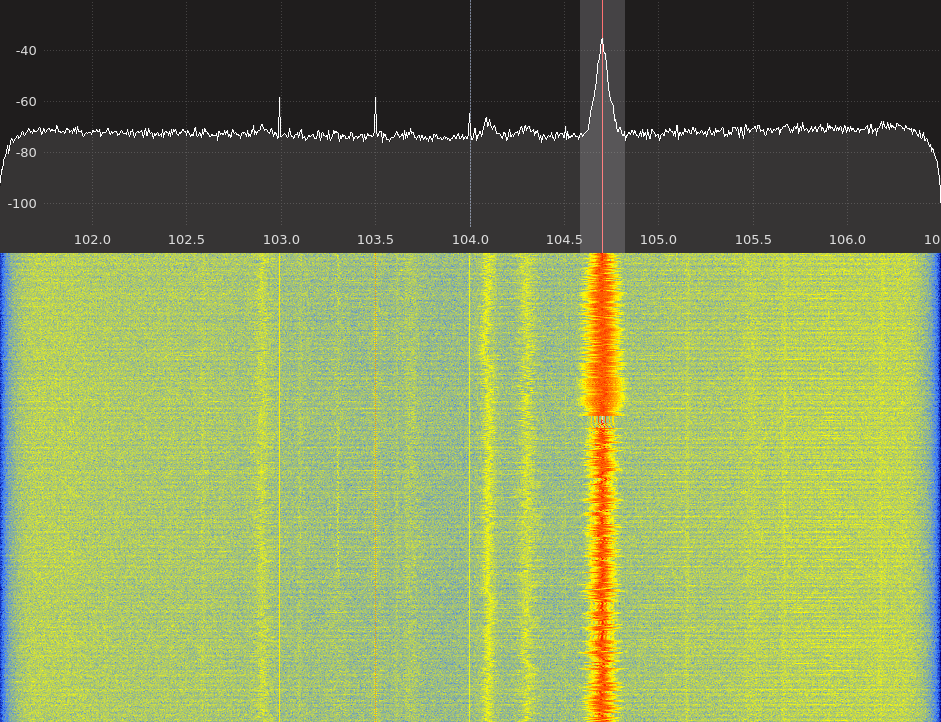

Consider the following image as an example. The very faint and almost invisible vertical lines are analogous to most detection capabilities we have. Because of that poor signal-to-noise ratio, we spend a significant amount of time and money trying to efficiently and consistently find bad things.

Figure 2. GNURadio GQRX – Signal-to-noise example

Because deception technologies are fake, there are no valid interactions to speak of. All interactions are suspicious and are either miss-configurations or bad people.

Our goal is to implement deception capabilities that provide signals as clear as the signal at 104.7MHz in the figure above.

A quick history

Deception is not a new idea, but I wanted to take a moment to provide some examples that show the creativity and artistry that is required along with the sometimes-surprising results of effective deception programs.

During the American civil war, at Corinth in May 1862, P.G.T. Beauregard was able to trick Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck into delaying an attack while the Confederates retreated. Beauregard used a series of ruses to deceive the Union force into thinking that not only was the Confederate force larger, but that they were being re-enforced throughout the night. This included running trains up and down the lines with soldiers cheering at each stop and dummy soldiers on the lines. In reality, Beauregard had spent the night withdrawing his troops, leaving an empty battlefield for Halleck.

| TIP | The best deceptions are 90% truth and 10% fiction. |

Figure 3. WWII Allied Ghost Army

In WWII, the British blunted the effectiveness of German navigational beacons use for bombing civilians through deception instead of jamming. They implemented ‘meacons’ that fooled the German pilots into bombing unpopulated areas (Handel, 1989, p. 164). Later in the war, during the invasion, the US Army’s 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, who specialized in “tactical deception” were very effective at fooling the Germans. Known as the “Ghost Army”, these Trojan Horse builders of World War II made rubber tanks and airplanes with elaborate costumes and trouped around France blasting speakers and sending radio messages giving the impression that the Allies had many more troops, tanks and airplanes.

The history of my experiences with deception technologies is far more current and much less interesting. Though I would argue that it does provide some context about my perspectives and biases about deception in the information security space.

I became interested in cyber deception in the mid 90’s and read Cliff Stoll’s “The Cuckoos Egg” and Bill Cheswick’ “An Evening with Berferd” with great interest, some years after they were published. Both involved deception with Cliff creating a fictitious department at LBNL to help catch an attacker and Bill creating a series of fake services on a system to stymie an attacker while watching what happened.

The Deception Toolkit [DTK][1] came out in 1997 and I played with it a fair amount. In 1998, Marus Ranum release BackOfficer Friendly though I never had a chance to shake it out. The Honeynet Project[2] got up and running 1999. It all came together for me with Tom Liston’s LaBrea: “Sticky” Honeypot and IDS[3]. I ended up working with Tom to make embedded OpenBSD appliances running laBrea that could be deployed on corporate networks. Then came Marcus Ranum, who pointed me to Specter IDS[4] in 2001. It was a nice honeypot for Windows that could impersonate different operating systems as well as services. The best part of the tool convinced me that I should never be responsible for designing user interfaces.

Figure 4. Specter IDS control interface

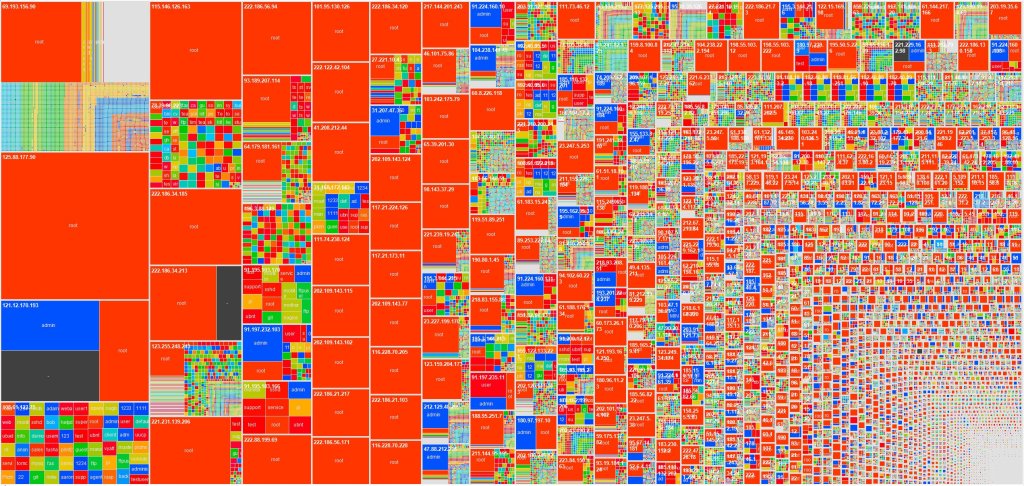

To this day, I still believe that Specter had the best UI ever created! For the next 13 years, I used a Frankenstein set of scripts, tools and applications to irritate and learn from attackers at home and on corporate networks. In 2014, I updated my personal honeypot infrastructure using Tom Liston’s HoneyPi images. It is so much easier to use someone else’s Frankenstein instead of maintaining your own. In 2017, I got tired of all the ssh brute forcing that was happening and created an ultra-low interaction ssh honeypot called sshCanary[5]. It ended up providing some interesting perspectives and visualizations about ssh brute force campaigns and tools.

Figure 5. Heatmap of ssh bruteforce attacks

More recently, Tom and I (mostly Tom) created a handy honeypot sensor that can impersonate all 65K TCP/UDP ports IPv4/IPv6, ICMP and some other protocols while running on a small embedded Linux device. This is thanks to the use of a novel implementation of what is essentially stateless TCP. This new sensor platform has greatly expanded the fidelity and effectiveness of honeypots.

General classes of deception

It is difficult to discuss the topic of deception without a common understanding and agreement on what deception is and through implication, what it is not. Marty Roesch provided a high-level classification of honeypots in 2002 that split the capability into two buckets. First are “production” honeypots that are deployed on private networks, focused on detecting anomalous or malicious activities and second are “research” honeypots that are deployed on public networks with the goal of collecting intelligence and evidence about malicious actors in the form of TTPs and IOCs. This is a nice and general classification though it is a bit coarse and does not fully address the current deception market.

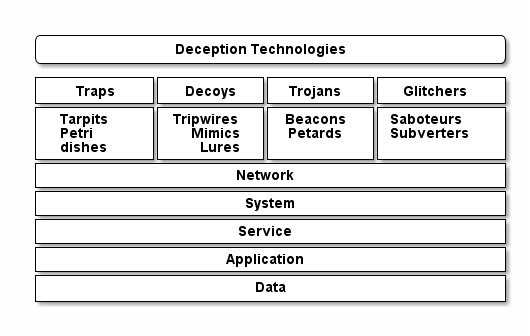

In the absence of a generally agreed upon taxonomy for deception, I propose that there are four classes of deception technology. Within each, are sub-categories or types that are specific to each class. For all classes and types or deception, there are implementation opportunities at various levels of the information technology stack.

Figure 6. Deception technology taxonomy

Classes

Traps are the first category of deception. As the name implies, these deception technologies are focused on trapping an adversary. The purpose of the trap can be to tilt the asymmetry in the favor of defenders by wasting the attackers time, reducing attack velocity, consuming their resources, or seeing what the attackers are doing. There are many good examples of traps that act like tarpits, but laBrea[6] is the epitome in name and functionality. When a laBrea tarpit is placed on the network, it consumes many unused IP addresses, responds to any communications to those addresses and logs all the traffic. When a TCP connection is established to the tarpit, laBrea uses the TCP Window size to trick the attacker into holding the connection open while limiting the amount of network traffic. For older scanning and attack code, laBrea was surprisingly effective at slowing or stopping automated propagation that depending on linear scanning of IP address ranges. Many security researchers use traps as petri dishes to watch and understand how attackers exploit and move through systems and infrastructure. The Honeynet Project[7] has been active since 1999 and published a book titled “Know Your Enemy: Learning about Security Threats” about their research in 2004.

Decoys are deception technologies designed to attract or entice malicious actors to interact. Differing from traps that are generally placed where a malicious actor is likely to stumble upon them, decoys are intentionally tempting targets. When deciding between traps and decoys, remember that traps are placed where the attackers are likely to find them. Decoys should be selected and placed with consideration of how to attract the attacker’s attention. Tripwires are the simplest decoys. They can be low-interaction technologies and they have a simple purpose; send an alarm when touched. The art of using tripwires involves the optimal implementation that only attackers will touch without raising suspicions. There is nothing more annoying than a tripwire that goes off constantly due to normal environmental activities. Currently, mimics are the most common commercial decoys. These solutions offer a variety of options for presenting fake devices, systems, services and even data. Some modern commercial solutions include dynamic impersonation of existing production capabilities. Attivo BOTSink[8] and thinkst Canary[9] provide these capabilities, supporting many platforms, operating systems and services. It can be difficult to differentiate lures, the last type of decoy, from tripwires and mimics. Lures are explicitly designed to pull an attacker to the decoy. Have you ever heard a security practitioner talking about someone finding a USB stick in the parking lot with “HR – RESTRICTED” written on it with a sharpie? The USB stick with the writing is the lure. Another similar example is placing a file named “Salary_data-DO_NOT_SHARE.xls” on a share with permissive access.

| WARNING | The higher the level of interaction, the greater the risk of exploitation and subversion. |

Traps and decoys are the most common and generally accepted deception technologies and can be considered passive in nature. The remaining classes are active and less common.

Arguably, the following two classes of deception with their active natures, can create controversy, illicit debate among security practitioners, and necessitate legal reviews prior to deployment. In addition, they can create opportunities for malicious subversion.

The third class of deception technologies and first that is active are trojans. The epic tale by Homer described the deception used by the Greeks to enter and conquer the city of Troy, thereby winning the Trojan war. For the purposes of our taxonomy, a deception technology that contains a component that actively responds when touched is a trojan. The way that the trojan responds determines if it is a beacon or a petard. As the names imply, the former sends intelligence about who did the touching and the latter explodes, hoisting whoever touched it into the air. With Legal review and approval, I have successfully used look-alike DNS domains served from servers with verbose monitoring paired with web and other beacons to locate the real point of origin of an attacker. Custom macros in Microsoft Office documents are still popular with the limitations of enabling macros. John Strand has written about Word web bugs that work without enabling macros. You are limited only by your imagination on ways to implement beacons. The limitations on petards has very little to do with the limits of your imagination and much more to do with your organizations tolerance for risk, it’s perspective on active measures, the specific scenario that you are considering and the opinions of your legal department. Significant attention should be focused on avoiding being hoisted by your own petard.

Last are Glitchers; these dedicated active deception technologies are uncommon with few vendors offering solutions. An argument can be made that some application aware firewall and intrusion prevention systems act as glitchers because they identify and interfere with network traffic that match known threat patterns. Glitchers can be split into two general types. First are saboteurs, where active response to a malicious action includes deliberate destruction, damage, or obstruction of the attack. I have heard of security practitioners setting up honeypots that redirect attack traffic back to the attackers IP address. I can only imagine the elation of an attacker successfully exploiting a victim, followed by the frustration of having their attack platform exploited by some unscrupulous internet ruffian for only the cost of a simple BPF[10] rule. Many years ago, when worms with IRC command-and-control were popular, I wrote a fake IRC C&C that sent the “uninstall” command to any newly infected machine that reported into my synthetic C&C IRC server. This glitcher sabotaged the botnet attack and effectively remediated infected machines automatically. A commercial solution by Trinity Cyber[11] provided for curated internet traffic, malicious action detection and sabotage as a service. The company claims that they watch the attack traffic, identify bad actors and key actions being attempted, then change the network session contents so that attacks do not work as expected. To conclude our taxonomy, subverters are the kinder and gentler type of glitchers. They have much in common with tarpits as their primary goal is to tilt the asymmetry in the favor of defenders by wasting the attackers time, reducing attack velocity, and consuming their resources. This is another opportunity to leverage the creativity and artistry of the defenders. A more appropriate name for this type of glitcher should be dirty tricks. And the question is, how can you mess with the attacker to waste their time. A few examples to stoke the creativity of the reader. If you detect an attempt to download a file, send a properly formatted file with gobs of random data. Event more annoying, send files with a false description of the encryption algorithm. If you can operate in the middle of a network connection, modify commands to benign or invalid versions and adjust return codes to report successes when actions fail.

| NOTE | The most significant advantage of deception capabilities comes from the amazing signal-to-noise ratio they offer. Though it is fun to waste the aggressors time while learning how they operate. |

Implementations

There are five general implementation categories for deception, and they are applicable across all classes and types of deception.

- Network – Deception through layer 4 in the OSI model[12].

- System – Deception at the operating system level.

- Service – Deception in services (e.g. DNS, SMTP, AD, etc.).

- Application – Deception in applications.

- Data – Deception in the data itself including files, structured and unstructured data.

Though these implementation categories are applicable to all the classes and types of deception, there are some categories that make more sense than others given a specific class or type of deception. For example, it is much more complicated, and perhaps impractical, to implement a data-based petri dish. On the other hand, System based petri dishes are the de facto standard.

An important and informative exercise is to take the list of deception classes, types and implementations and consider the totality of your environment. Then fill in as many of the boxes as you can with deception capabilities, opportunities, and possibilities. We will review this exercise later.

| NOTE | Network based deception is the hardest to detect. As you move up the stack it gets easier for the adversary to spot, making application and data-based deception the most likely to be discovered. |

Effective multi-modal deception

If you want to improve the effectiveness of your deception capabilities, consider how you can combine different classes, types, and implementations. Vendors are developing deception systems that do just that. Solutions like Attivo support traps and decoys that will work together to attract and funnel attackers past tripwires using lures so that they land in tarpits and petri dishes.

A holistic deception program will include a thoughtful organization of capabilities and how they interact to maximize fidelity and sensitivity. Implement monitoring, metrics and reporting to judge the effectiveness of the program. Additionally, some game theory focused approaches have been presented in recent years to further evaluate the effectiveness of deception GAME and adaptive deception SPAWAR strategies.

Internal vs. external

Most deception capabilities should be implemented within non-public zones of control. This is recommended to help protect the high signal-to-noise ratio offered by deception while limiting the exposure of additional attack surfaces along with their ongoing maintenance requirements.

External deception capabilities should be very limited and focused on petri dishes implemented to answer specific questions about attack vectors, TTPs and IOCs.

| TIP | Deploying external facing deception capabilities greatly reduces their signal-to-noise ratio while exposing yourself to asymmetric attacks including resource consumption. |

Active defense

A quick reminder about the major risk of counter attacks. The adversaries are smart and determined. They will figure out if active defenses exist. When they find them, they will try to subvert them, and it will be difficult to explain how and why a defensive mechanism was used to attack the innocent.

| CAUTION | Automated response can be subverted and exploited. Be very sure before acting against an aggressor. |

Look into active defenses after you have rolled out most passive deception capabilities. There is surprising value to be had from passive deception. Put some points on the board with passive capabilities before delving too deeply into active deception capabilities.

Deception as a program

I began with an assertion about our adversary’s business. A deception program needs to start by acknowledging the truth about their business goals and quickly pivot to the question of what we can do about it.

I suggest that your deception program’s motto should be “Non est aequus”. This comes from a friend who had an interesting and funny experience while presenting penetration test findings in front of a large audience of engineers responsible for designing the systems being tested. He described bypassing all the amazing security controls that the company had implemented by physically stealing a device, removing the circuit board and extracting very sensitive authentication tokens directly from the hardware. When he concluded, a senior engineer in the audience stood up and yelled out “THAT’S NOT FAIR!”.

NON EST AEQUUS

My challenge to you as the reader is to move forward with a holistic deception program that lives by that motto with creativity and artistry that continually confuses and frustrates the adversaries. And as you do, encourage, coach, mentor, and train others to do the same!

A lack of Sun Tzu quotes was brought to my attention while putting this together. Feedback is a gift and I feel obligated to oblige with a Sun Tzu quote. I present this quote in Latin to address concerns about missing another stereotypical infosec crutch.

“Omne bellum est deceptio” -Sun Tzu

Additional reading

- Know your enemy from the honeynet project is very good.

- Offensive countermeasures by John Strand.

References

- [WRCDS] Wellington Research. (2019, June). Cyber Deception Systems Market Segment Report. Retrieved from https://wellingtonresearch.com/the-market-for-cds/

- [DW] Dan Woods (2018, Jun 22). How Deception Technology Gives You The Upper Hand In Cybersecurity. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/danwoods/2018/06/22/how-deception-technology-gives-you-the-upper-hand-in-cybersecurity/#1d249f19689e

- [MM] Mohssen Mohammed & Habib-ur Rehman. Honeypots and Routers Collecting Internet Attacks. CRC Press. 2015.

- [TCE] Clifford Stoll. The Cuckoo’s Egg: Tracking a Spy Through the Maze of Computer Espionage. Pocket Books, New York. 1990.

- [CHEZ] Bill Cheswick (1991, Jan 7). An Evening with Berferd. Retrieved from https://www.cheswick.com/ches/papers/berferd.pdf

- [LS] Lance Spitzner. Honeypots: Tracking Hackers. Addison-Wesley. 2002.

- [JS] John Strand & Paul Asadoorian. Offensive Countermeasures: The Art of Active Defense. PaulDotCom. 2015.

- [CW] Maurice D’Aoustand (2016, June). Hoodwinked During America’s Civil War: Confederate Military Deception. Retrieved from https://www.historynet.com/hoodwinked-during-americas-civl-war-confederate-military-deception.htm

- [WW2] Megan Garber (2013, May 22). Ghost Army: The Inflatable Tanks That Fooled Hitler. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/05/ghost-army-the-inflatable-tanks-that-fooled-hitler/276137/

- [SSM] Simon Sebag Montefiore. Catherine the Great and Potemkin. Penguin Random House LLC. 2001.

- [LS2] Lance Spitzner (2002, Oct 3). Definitions and Value of Honeypots. Retrieved from https://www.eetimes.com/definitions-and-value-of-honeypots/#

- [MK] Maria Korolov (2016, Aug 29). Deception technology grows and evolves. Retrieved from https://www.csoonline.com/article/3113055/deception-technology-grows-and-evolves.html

- [KYE] The Honeynet Project. Know Your Enemy: Learning about Security Threats. Addison-Wesley. 2004.

- [ILL] Homer. The Iliad. Translated by J. Davies. Introduction and notes by D. Wright. London: Dover Publications. 1997.

- [MH] Michael I. Handel. War, Strategy and Intelligence. U.S. Army War College. 1989.

- [JS2] John Strand (2020, Apr 13). Tracking Attackers With Word Web Bugs (Cyber Deception). Retrieved from https://www.blackhillsinfosec.com/tracking-attackers-with-word-web-bugs-cyber-deception/

- [SPAWAR] Kimberly Ferguson-Walter & Sunny Furgate & Justin Mauger & Maxine Major (2019. Apr 1-3). Game Theory for Adaptive Defensive Cyber Deception. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331357854_Game_Theory_for_Adaptive_Defensive_Cyber_Deception

- [GAME] Aaron Schlenker, Omkar Thakoor, Haifeng Xu, Milind Tambe, Phebe Vayanos & Fei Fang & Long Tran-Thanh & Yevgeniy Vorobeychik (2018, July). Deceiving Cyber Adversaries: A Game Theoretic Approach. Retrieved from https://www.cais.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/deceiving-cyber-adversaries.pdf

1. DTK – http://www.all.net/dtk/dtk.html

2. The Honeynet Project – https://www.honeynet.org/

3. LaBrea – https://labrea.sourceforge.io/

5. sshCanary – https://github.com/rondilley/sshcanary

6. LaBrea – https://labrea.sourceforge.io/

7. The Honeynet Project – https://www.honeynet.org/

8. https://attivonetworks.com/product/attivo-botsink/

9. thinkst Canary – https://canary.tools/

10. Berkeley Packet Filter – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berkeley_Packet_Filter

11. Trinity Cyber – https://www.trinitycyber.com/

12. OSI Model – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OSI_model

Leave a comment